氧化亚氮在口腔颌面外科手术中的抗维生素作用——叙述性综述

简介

背景

作为牙科治疗的辅助手段,氧化亚氮(N2O)是第一种引起公众注意的吸入麻醉药。如今,大多数用于口腔颌面(OMF)手术的吸入式麻醉药都包含了这种气体。但它的抗维生素作用一般都被忽视了。因此,本综述的主要目的是阐明这种通常不易察觉但可检测到的毒性。

1772年,在硝酸盐溶液作用于金属产生的气泡中,人们发现了N2O。1799年,Humphry Davy发现这种纯净的气体无刺激性且会使人产生醉意[1,2]。他在伦敦的皇家学会进行了演示,并大受好评,这种物质开始作为“笑气”广为人知[1]。

医学生Gardner Quincy Colton在美国进行了笑气展示[3,4]。1844年,美国牙医Horace Wells观看了Colton的展示后,提出了用N2O进行无痛拔牙的建议[5]。Wells没能使哈佛医学院的见证者相信N2O是一种有效的麻醉药[5],但他的搭档William T.G. Morton在那里成功地演示了相对有效的乙醚蒸汽[6]。Morton在1846年10月16日进行的OMF手术(即切除下颚肿瘤手术)中所作的乙醚麻醉演示具有里程碑意义。尽管Morton在“乙醚日”取得了成功,但Colton仍坚持使用含氮物质,并成为曼哈顿最繁忙的无痛牙科医生[4]。

哈佛大学最后一次使用乙醚麻醉药是在1978年,而N2O时至今日仍然是一种经常使用的麻醉药。然而,这种气体会损害维生素B12的功能。它能使甲硫氨酸合酶共价失活,而甲硫氨酸合酶是人类两个重要的B12酶之一。

原理和知识差距

我们考虑抗维生素现象作用的机制和临床影响。

目标

我们考虑N2O存在可观毒性的情况。

我们根据叙述性综述报告清单(可在https://joma.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/joma-22-21/rc获取)撰写这篇文章。

方法

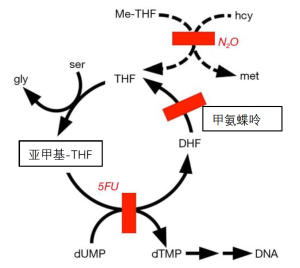

通过美国国家医学图书馆的PubMed搜索引擎,在MEDLINE数据库中检索了1956年—2022年的英文参考文献和摘要(表1)。全文通过哈佛医学院的Countway图书馆获取。以SANRA标准为准则。

Full table

研究内容

抗维生素作用

N2O对维生素B12产生拮抗作用的证据出现在1956年[7]。需要机械通气、镇静和镇痛的破伤风患者用50%的N2O通气数天后,外周血涂片上出现了巨幼红细胞[7]。巨幼红细胞是大的、有核的红细胞前体。它们通常不在循环中出现,但在所谓的恶性贫血中特别突出[7]。恶性贫血在19世纪被认为是一种贫血性疾病,通常在出现症状的三年内就会死亡。这种疾病使得维生素B12在20世纪90年代被发现,挽救了许多生命。相应地,因使用N2O而暴露导致的巨幼红细胞增多症提示了维生素B12的功能不足[7]。

甲硫氨酸合酶

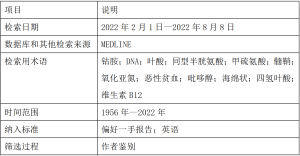

人体内有两种维生素B12依赖的酶。它们是甲硫氨酸合酶(图1)和甲基丙二酰辅酶A变位酶。其中前者可以被N2O共价灭活。合成酶的反应的化学式(1)如下。

甲基四氢叶酸+同型半胱氨酸→四氢叶酸+甲硫氨酸 (1)

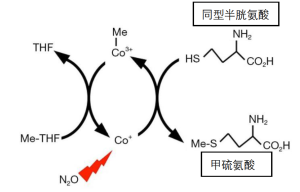

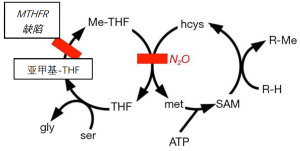

甲硫氨酸是构成蛋白质的20种氨基酸之一。它是一种“必需”氨基酸,通过饮食摄取。那么,为什么甲硫氨酸合酶在人类的新陈代谢中很重要?因为甲硫氨酸是一种S-甲基化合物,是生物合成中单碳基(甲基)的重要来源(图2)。新陈代谢中的许多甲基化需要消耗甲硫氨酸,然后在所谓的甲硫氨酸循环中由甲硫氨酸合酶重新合成。例如,去甲肾上腺素通过N-甲基转移酶甲基化为肾上腺素,而儿茶酚胺通过O-甲基转移酶甲基化后失活。由甲硫氨酸产生的甲基的其他例子还有乙酰胆碱和含胆碱的脂质。胆汁中的卵磷脂是一种含胆碱的脂质(这就是乙酰胆碱一词和胆囊切除术的英文单词发音近似的历史原因)。另一种由胆碱衍生的脂质是鞘磷脂,是神经髓鞘的主要成分。间接涉及甲硫氨酸合成酶的甲基化是尿嘧啶成为DNA胸腺嘧啶的过程(图3)。

维生素B12分子含有一个钴离子,因此也被称为钴胺。在维生素药片中,该分子被一个功能不活跃的氰化物基团所稳定,也被称为氰钴胺。氰钴胺的钴原子处于氧化的三价状态(Co3+),不会被N2O进一步氧化。然而,在甲硫氨酸合酶的催化活性部位,不含氰化物的钴以不稳定的Co1+状态发挥作用(图1)。在没有蛋白质的保护下,高活性的一价钴可以将水还原成氢气。在麻醉药浓度下,N2O可以与活性钴原子发生反应。N2O通过一个电子被还原成一个羟自由基(HO-),然后使酶的一个重要部分失活[8]。羟基自由基的产生详见公式(2)。

Co1++N2O+H+→CO2++N2+HO (2)

受损的酶不能被修复,恢复需要氨基酸从头合成新的酶分子,这个过程在人体内需要几天的时间[8,9]。酶的失活率并不确切,而且这一过程在体内可能不是单相的。啮齿动物相对敏感,可能是由于代谢率高。人类的肝脏活检显示,大约一半的酶在几小时内被50%~70%的含氮物质灭活[9]。

甲基丙二酰辅酶A变位酶参与脂肪酸和氨基酸的分解,产生丙酸(CH3-CH2-COOH)。该酶不与N2O直接反应。然而,长期暴露在N2O中可能会间接降低突变酶的水平,因为钴胺在甲硫氨酸合酶与N2O的反应中被消耗了。变位酶的辅因子是一种被称为腺苷钴胺的维生素B12形式,目前尚不清楚N2O是否会影响钴胺的腺苷化。

甲硫氨酸合酶失活的后果

甲硫氨酸合酶失活至少有三个后果:DNA合成抑制、神经病变和血浆同型半胱氨酸的升高。

DNA合成受到抑制是因为甲硫氨酸合酶参与了胸腺嘧啶与DNA的结合(图3)。饮食中的胸腺嘧啶在DNA的合成中利用率很低。相反,一个脱氧尿核苷酸被甲基化为一个胸腺嘧啶。暴露于N2O后的DNA合成抑制已在人类身上得到证实,这是用一种称为脱氧尿苷抑制试验的体外细胞检测方法,其中脱氧尿苷会抑制放射性标记的胸腺嘧啶合成DNA[10]。其他证据包括巨幼红细胞增多症和巨幼红细胞性贫血的病例[11]。

在未经治疗的恶性贫血中,N2O与脊髓脱髓鞘的病变有关[11-17]。N2O还与其他神经疾病[18-21]和精神问题[22-27]有关,患者中毒风险增加。脱髓鞘可能是因为甲硫氨酸合酶为鞘磷脂分子提供甲基(图2)。该酶还为乙酰胆碱、肾上腺素和O-甲基儿茶酚胺提供甲基。

甲硫氨酸合酶的体外检测很麻烦,最适合采用固体组织的活检标本。因此,关于人体内酶的失活和再生的动力学只有大致了解。然而,N2O的急性代谢作用很容易被检测到,因为血浆中的同型半胱氨酸水平增加[28-34]。同型半胱氨酸是合酶反应中甲硫氨酸的前体(图1)。

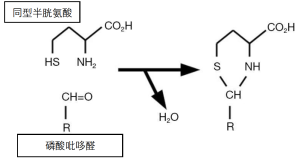

尽管同型半胱氨酸是一个重要的代谢中间物,但其浓度升高具有毒性。首先,该分子会自发形成磷酸吡哆醇的稳定共价衍生物,即维生素B6(吡哆醇)的酶活性形式(图4)[35,36]。加合物的形成耗尽了磷酸吡哆醇(吡哆醇的酶辅因子形式),而且加合物是磷酸吡哆醇依赖性酶的抑制剂。这些酶包括丝氨酸羟甲基转移酶,它将四氢叶酸转换为亚甲基四氢叶酸(图2~图3)。因此,维生素B12的功能受损破坏了维生素B6(吡哆醇)和B9(叶酸)的功能。

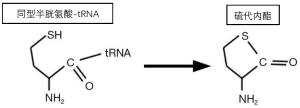

同型半胱氨酸毒性的另一个机制涉及其代谢为化学反应产物。通常将甲硫氨酸附着在tRNA上的ATP利用型合酶,也将同型半胱氨酸附着在tRNA上。甲硫氨酸-tRNA用于蛋白质的合成,但同型半胱氨酸-tRNA是不稳定的(图5)。它产生的环状硫代内酯被称为同型半胱氨酸硫代内酯[37]。这种硫代内酯可以非特异性地附着在细胞成分上,并特异性地阻断赖氨酸氧化酶的活性部位,赖氨酸氧化酶是一种参与血管和其他结缔组织中胶原蛋白和弹性蛋白链交联的酶[38]。

赖氨酸氧化酶的失活可能促进同型半胱氨酸的动脉粥样硬化作用[39]。然而,这一作用和促血栓作用可能涉及硫代内酯和(或)同型半胱氨酸与其他反应[20,39-42]。例如,它们影响血管内皮。特别是,它们抑制内皮产生一氧化氮(NO),这是一个双原子的气体分子,不能与三原子的麻醉药N2O相混淆。1997年诺贝尔奖的主题就是NO能抑制血小板的粘附和聚集,并能扩张血管。除了抑制内皮细胞的NO合成外,硫化合物如同型半胱氨酸直接与NO反应,从而清除NO[28]。

心血管并发症已被归因于慢性同型半胱氨酸血症[39,40]。然而,ENIGMA-Ⅱ研究表明,在已知或怀疑有冠状动脉疾病的非心脏手术患者中,将一次性使用N2O作为一部分的麻醉方案具有长期安全性[43,44]。

N2O毒性的风险因素

N2O被用作麻醉药时,很少出现严重的代谢问题。中毒的风险因素包括长期接触[24,45,46];甲氨蝶呤和相关药物治疗[47-49];遗传问题,如缺乏亚甲基四氢叶酸还原酶;恶性贫血[7,11];日常饮食中可能缺乏维生素。

长期接触N2O的原因可能包括娱乐性滥用麻醉药物[24]以及职业性接触[45]。娱乐性接触可能涉及被称为whippits或whippets的小瓶气体。这些气体可以用来为烹饪打发奶油。该制剂在减压时被排放到气球中供人吸入。职业性接触最可能发生在通过松散的面罩接受气体的患者中。甲硫氨酸合酶的失活在麻醉药停用后持续存在,因此毒性可能来自长时间的麻醉药使用或是重复接触[46]。

甲氨蝶呤抑制二氢叶酸还原酶,而N2O使甲硫氨酸成酶失活。这两种酶都会产生四氢叶酸,因此,这两种抑制剂的结合会对四氢叶酸在DNA合成中的参与造成严重损害。在实验室的啮齿动物实验中,很容易证明N2O可以将非致死剂量的甲氨蝶呤转化为致死剂量[47]。在人类中也遇到过N2O对甲氨蝶呤的增效作用[48,49]。

叶酸或维生素B12代谢中的任何遗传缺陷都可能容易导致N2O的毒性。一个例子是缺乏亚甲基-四氢叶酸还原酶[12,50-53]。以恶性贫血的为例,B12或叶酸的缺乏也会增加N2O的毒性[54]。蛋白质和(或)维生素的营养消耗也会增加N2O的代谢并发症的可能性[55-57]。术前补充维生素B12可减少术后同型半胱氨酸的升高[35,58],但效果不一[59]。

治疗/抢救

恶性贫血的一个教训是,维生素B12的缺乏可以通过补充来缓解。例如,早期恶性贫血的贫血症状可以被一定剂量的叶酸所掩盖。令人遗憾的是,尽管补充了叶酸,该病的神经病变仍在继续。应对策略之一是提供补充的四氢叶酸。然而,该分子在氧气存在下非常不稳定。因此,四氢叶酸是以一种相对稳定的衍生物形式提供的,称为亚叶酸[60,61]。在化学上被称为N-甲酰四氢叶酸。该分子于1948年被发现为柠檬酸杆菌的一种基本生长因子酸,因此它被称为柠檬酸杆菌因子,也被称为白藜芦醇。它在临床上被引入用于解救甲氨蝶呤。在二氢叶酸还原酶或甲硫氨酸合酶的抑制剂存在的情况下,它允许一些DNA合成(图3)。然而,完全实现抢救还需要让它在体内再循环,而再循环会因上述酶抑制剂的存在而受到抑制。

外源性胸腺嘧啶碱很少用于DNA合成[62-65],但鉴于在治疗恶性贫血中看到的好处,胸腺嘧啶核苷值得作为一种救援剂进行研究[66]。由于髓鞘的鞘磷脂是一种胆碱酯,研究饮食中的胆碱对预防N2O引起的脱髓鞘有重要意义[67]。

饮食中补充外源性甲硫氨酸和甜菜碱(N,N,N-三甲基甘氨酸)可以缓和钴胺代谢的错误[68]。最常见的情况是钴胺C紊乱,在这种情况下,饮食中的氰钴胺和其他形式的维生素B12不能转化为甲硫氨酸合酶的酶活性形式(也不能转化为甲基丙二酰辅酶A变位酶)。一个早期发病的患者持续服用甲硫氨酸和甜菜碱时,甲硫氨酸水平会被提高到正常水平[69]。蛋氨酸水平正常化可以防止与钴胺C紊乱有关的中枢神经系统后遗症,包括脊髓的亚急性联合变性(subacute combined degeneration,SCD)[69]。然而,这些发现还没有在人类身上得到很好的研究。补充甲硫氨酸对接触N2O的猴子和猪的SCD有保护作用[70,71]。

因为在甲硫氨酸合酶与N2O的反应中,钴胺辅因子被共价消耗,所以在使用N2O之前或之后,服用维生素B12似乎是有益的。如果维生素B12的缺乏在临床上很明显,那么维生素B12显然是适用的。

理论上的考虑

鉴于甲硫氨酸合酶的Co1+中心的强氧化-还原电位,除N2O外,其他氧化剂也可能与该酶发生反应。除了N2O之外,另一种已知能使甲硫氨酸合酶失活的药物是氯仿[72-75]。氯仿对甲硫氨酸合成的失活在一个依赖B12的大肠杆菌菌株中得到证实,此前人们注意到氯仿和相关的分子在牛的瘤胃居住的细菌中阻止了依赖B12的甲烷生物合成[76-78]。耐人寻味的是,N2O或氯仿是否可能对依赖B12的病原体微生物具有可利用的抗生素活性。例如,疟疾寄生虫携带一种依赖B12的甲硫氨酸合酶[79]。目前,还没有N2O作为抗菌药物的例子,而且以麻醉剂量吸入N2O也不能作为抗厌氧菌的策略[46,80]。

N2O对正在分裂的肿瘤细胞有选择性的毒性[46,78-85]。考虑到皮肤对吸入性麻醉药的渗透性[86],评估该气体对皮肤病变的局部治疗是很有意义的。

结论

可吸入的N2O是一种有用的、普遍安全的麻醉药。然而,它具有拮抗维生素B12的功能,而维生素B12是参与DNA合成、神经髓鞘化和同型半胱氨酸清除的因素。因此,谨慎的做法是避免长期或重复接触作为麻醉药/镇静药的N2O。在出现神经病变和相关代谢损伤的情况下,如并发甲氨蝶呤治疗、亚甲基四氢叶酸还原酶的遗传缺陷、恶性贫血和营养不良等情况下,应考虑使用替代麻醉药。然而,无论是常规的维生素B12状态筛查,还是补充维生素B12,都不太可能对于几小时或更短的一次性麻醉接触产生临床价值。

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Jingping Wang and Christopher Fanelli) for the series “Opioid-free Anesthesia and Opioid-sparing Anesthesia in OMF Surgery” published in Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Anesthesia. The article has undergone external peer review.

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the Narrative Review reporting checklist. Available at https://joma.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/joma-22-21/rc

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://joma.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/joma-22-21/coif). The series “Opioid-free Anesthesia and Opioid-sparing Anesthesia in OMF Surgery” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Davy H. Researches, Chemical and Philosophical; Chiefly Concerning Nitrous Oxide: Or Dephlogisticated Nitrous Air, and its Respiration. London, UK: J. Johnson; 1800.

- Alston TA. Early misconceptions about nitrous oxide, an "invigorating" asphyxiant. J Clin Anesth 2010;22:59-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Smith GB, Hirsch NP. Gardner Quincy Colton: pioneer of nitrous oxide anesthesia. Anesth Analg 1991;72:382-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yang QH, Alston TA, Phineas T. Barnum, Gardner Q. Colton, and Painless Parker Were Kindred Princes of Humbug. J Anesth Hist 2019;5:13-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haridas RP. Horace wells' demonstration of nitrous oxide in Boston. Anesthesiology 2013;119:1014-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fenster JM. Ether Day: The Strange Tale of America's Greatest Medical Discovery and the Haunted Men Who Made It. New York, NY: HarperCollins; 2002.

- Lassen HC, Henriksen E, Neukirch F, et al. Treatment of tetanus; severe bone-marrow depression after prolonged nitrous-oxide anaesthesia. Lancet 1956;270:527-30. [PubMed]

- Drummond JT, Matthews RG. Nitrous oxide inactivation of cobalamin-dependent methionine synthase from Escherichia coli: characterization of the damage to the enzyme and prosthetic group. Biochemistry 1994;33:3742-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Koblin DD, Waskell L, Watson JE, et al. Nitrous oxide inactivates methionine synthetase in human liver. Anesth Analg 1982;61:75-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Amess JA, Burman JF, Rees GM, et al. Megaloblastic haemopoiesis in patients receiving nitrous oxide. Lancet 1978;2:339-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hogue CW Jr, Perese D, Vacanti CA, et al. Potential toxicity from prolonged anesthesia: a case report of a thirty-hour anesthetic. J Clin Anesth 1990;2:183-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yu M, Qiao Y, Li W, et al. Analysis of clinical characteristics and prognostic factors in 110 patients with nitrous oxide abuse. Brain Behav 2022;12:e2533. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Garakani A, Jaffe RJ, Savla D, et al. Neurologic, psychiatric, and other medical manifestations of nitrous oxide abuse: A systematic review of the case literature. Am J Addict 2016;25:358-69. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Check L, Abdelsayed N, Figueroa G, et al. Subacute Combined Degeneration of the Cervical Spine Secondary to Inhaled Nitrous-Oxide-Induced Cobalamin Deficiency. Cureus 2022;14:e21214. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Agarwal P, Khor SY, Do S, et al. Recreational Nitrous Oxide-Induced Subacute Combined Degeneration of the Spinal Cord. Cureus 2021;13:e19377. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cao J, Ran L, Liu C, et al. Serum copper decrease and cerebellar atrophy in patients with nitrous oxide-induced subacute combined degeneration: two cases report. BMC Neurol 2021;21:471. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Berling E, Fargeot G, Aure K, et al. Nitrous oxide-induced predominantly motor neuropathies: a follow-up study. J Neurol 2022;269:2720-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Richardson PG. Peripheral neuropathy following nitrous oxide abuse. Emerg Med Australas 2010;22:88-90. [PubMed]

- Thompson AG, Leite MI, Lunn MP, et al. Whippits, nitrous oxide and the dangers of legal highs. Pract Neurol 2015;15:207-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kuipers RS, Paes AJ, Amoroso G, et al. Thrombosis within the left anterior descending coronary artery and left ventricle after high-dose nitrous oxide use. BMJ Case Rep 2022;15:e248281. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sluyts Y, Vanherpe P, Amir R, et al. Vitamin B(12) deficiency in the setting of nitrous oxide abuse: diagnostic challenges and treatment options in patients presenting with subacute neurological complications. Acta Clin Belg 2022;77:955-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Singh SK, Misra UK, Kalita J, et al. Nitrous oxide related behavioral and histopathological changes may be related to oxidative stress. Neurotoxicology 2015;48:44-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sethi NK, Mullin P, Torgovnick J, et al. Nitrous oxide "whippit" abuse presenting with cobalamin responsive psychosis. J Med Toxicol 2006;2:71-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Levine J, Chengappa KN. Exposure to nitrous oxide may be associated with high homocysteine plasma levels and a risk for clinical depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2007;27:238-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pedersen OB, Hvas AM, Grove EL A. 19-Year-Old Man with a History of Recreational Inhalation of Nitrous Oxide with Severe Peripheral Neuropathy and Central Pulmonary Embolism. Am J Case Rep 2021;22:e931936. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xiang Y, Li L, Ma X, et al. Recreational Nitrous Oxide Abuse: Prevalence, Neurotoxicity, and Treatment. Neurotox Res 2021;39:975-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu G, Wang S, Wang T, et al. Neurological and Psychological Characteristics of Young Nitrous Oxide Abusers and Its Underlying Causes During the COVID-19 Lockdown. Front Public Health 2022;10:854977. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Myles PS, Chan MT, Kaye DM, et al. Effect of nitrous oxide anesthesia on plasma homocysteine and endothelial function. Anesthesiology 2008;109:657-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Myles PS, Chan MT, Leslie K, et al. Effect of nitrous oxide on plasma homocysteine and folate in patients undergoing major surgery. Br J Anaesth 2008;100:780-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nagele P, Tallchief D, Blood J, et al. Nitrous oxide anesthesia and plasma homocysteine in adolescents. Anesth Analg 2011;113:843-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cascella M, Arcamone M, Morelli E, et al. Multidisciplinary approach and anesthetic management of a surgical cancer patient with methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase deficiency: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep 2015;9:175. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kiasari AZ, Firozian A, Baradari AG, et al. The effect of vitamin B12 infusion on prevention of nitrous oxide-induced homocysteine increase: a double-blind randomized control trial. Oman Med J 2014;29:194-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pichardo D, Luginbuehl IA, Shakur Y, et al. Effect of nitrous oxide exposure during surgery on the homocysteine concentrations of children. Anesthesiology 2012;117:15-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nagele P, Zeugswetter B, Eberle C, et al. A common gene variant in methionine synthase reductase is not associated with peak homocysteine concentrations after nitrous oxide anesthesia. Pharmacogenet Genomics 2009;19:325-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pestaña A, Sandoval IV, Sols A. Inhibition by homocysteine of serine dehydratase and other pyridoxal 5'-phosphate enzymes of the rat through cofactor blockage. Arch Biochem Biophys 1971;146:373-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Głowacki R, Stachniuk J, Borowczyk K, et al. Quantification of homocysteine and cysteine by derivatization with pyridoxal 50 -phosphate and hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography. Anal Bioanal Chem 2016;408:1935-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jakubowski H. Homocysteine thiolactone: metabolic origin and protein homocysteinylation in humans. J Nutr 2000;130:377S-81S. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu G, Nellaiappan K, Kagan HM. Irreversible inhibition of lysyl oxidase by homocysteine thiolactone and its selenium and oxygen analogues. Implications for homocystinuria. J Biol Chem 1997;272:32370-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bełtowski J. Protein homocysteinylation: a new mechanism of atherogenesis? Postepy Hig Med Dosw (Online) 2005;59:392-404. [PubMed]

- Yilmaz N. Relationship between paraoxonase and homocysteine: crossroads of oxidative diseases. Arch Med Sci 2012;8:138-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oulkadi S, Peters B, Vliegen AS. Thromboembolic complications of recreational nitrous oxide (ab)use: a systematic review. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2022;54:686-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Valck L, Defelippe VM, Bouwman NAMG. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: a complication of nitrous oxide abuse. BMJ Case Rep 2021;14:e244478. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Leslie K, Myles PS, Kasza J, et al. Nitrous oxide and serious long-term morbidity and mortality in evaluation of nitrous oxide in the gas mixture for anaesthesia (ENIGMA)-II trial. Anesthesiology 2015;123:1267-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Myles PS, Leslie K, Chan MT, et al. The safety of addition of nitrous oxide to general anaesthesia in at-risk patients having major non-cardiac surgery (ENIGMA-II): a randomized, single-blind trial. Lancet 2014;384:1446-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Krajewski W, Kucharska M, Pilacik B, et al. Impaired vitamin B12 metabolic status in healthcare workers occupationally exposed to nitrous oxide. Br J Anaesth 2007;99:812-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen Y, Liu X, Cheng CH, et al. Leukocyte DNA damage and wound infection after nitrous oxide administration: a randomized controlled trial. Anesthesiology 2013;118:1322-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ermens AA, Schoester M, Spijkers LJ, et al. Toxicity of methotrexate in rats preexposed to nitrous oxide. Cancer Res 1989;49:6337-41. [PubMed]

- Fiskerstrand T, Ueland PM, Refsum H. Folate depletion induced by methotrexate affects methionine synthase activity and its susceptibility to inactivation by nitrous oxide. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1997;282:1305-11. [PubMed]

- Löbel U, Trah J, Escherich G. Severe neurotoxicity following intrathecal methotrexate with nitrous oxide sedation in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2015;62:539-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Selzer RR, Rosenblatt DS, Laxova R, et al. Adverse effect of nitrous oxide in a child with 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase deficiency. N Engl J Med 2003;349:45-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gerges FJ, Dalal AR, Robelen GT, et al. Anesthesia for cesarean section in a patient with placenta previa and methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase deficiency. J Clin Anesth 2006;18:455-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nagele P, Brown F, Francis A, et al. Influence of nitrous oxide anesthesia, B-vitamins, and MTHFR gene polymorphisms on perioperative cardiac events: the vitamins in nitrous oxide (VINO) randomized trial. Anesthesiology 2013;119:19-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nagele P, Zeugswetter B, Wiener C, et al. Influence of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene polymorphisms on homocysteine concentrations after nitrous oxide anesthesia. Anesthesiology 2008;109:36-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Singer MA, Lazaridis C, Nations SP, et al. Reversible nitrous oxide-induced myeloneuropathy with pernicious anemia: case report and literature review. Muscle Nerve 2008;37:125-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ahn SC, Brown AW. Cobalamin deficiency and subacute combined degeneration after nitrous oxide anesthesia: a case report. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2005;86:150-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Felmet K, Robins B, Tilford D, et al. Acute neurologic decompensation in an infant with cobalamin deficiency exposed to nitrous oxide. J Pediatr 2000;137:427-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beltramello A, Puppini G, Cerini R, et al. Subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord after nitrous oxide anaesthesia: role of magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1998;64:563-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Badner NH, Freeman D, Spence JD. Preoperative oral B vitamins prevent nitrous oxide-induced postoperative plasma homocysteine increases. Anesth Analg 2001;93:1507-10. table of contents. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rao LK, Francis AM, Wilcox U, et al. Pre-operative vitamin B infusion and prevention of nitrous oxide-induced homocysteine increase. Anaesthesia 2010;65:710-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Amos RJ, Amess JA, Nancekievill DG, et al. Prevention of nitrous oxide-induced megaloblastic changes in bone marrow using folinic acid. Br J Anaesth 1984;56:103-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Palmer AM, Kamynina E, Field MS, et al. Folate rescues vitamin B(12) depletion-induced inhibition of nuclear thymidylate biosynthesis and genome instability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017;114:E4095-102. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Plentl AA, Schoenheimer R. Studies in the metabolism of purines and pyrimidines by means of isotopic nitrogen. J Biol Chem 1944;153:203-17. [Crossref]

- Welch AD, Heinle RW. Hematopoietic agents in macrocytic anemias. Pharmacol Rev 1951;3:345-411. [PubMed]

- Spies TD, Frommeyer WB Jr. Anti-anemic properties of thymine. Blood 1946;1:185-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vilter RW, Horrigan D, Mueller JF, et al. Studies on the relationships of vitamin B12, folic acid, thymine, uracil and methyl group donors in persons with pernicious anemia and related megaloblastic anemias. Blood 1950;5:695-717. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hausmann K. Haemopoietic effect of thymidine in pernicious anaemia. Lancet 1951;1:329-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bennett MA. Some observations on the role of folic acid in utilization of homocystine by the rat. Science 1949;110:589. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Christensen B, Guttormsen AB, Schneede J, et al. Preoperative methionine loading enhances restoration of the cobalamin-dependent enzyme methionine synthase after nitrous oxide anesthesia. Anesthesiology 1994;80:1046-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Smith SE, Kinney HC, Swoboda KJ, et al. Subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord in cbIC disorder despite treatment with B12. Mol Genet Metab 2006;88:138-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weir DG, Keating S, Molloy A, et al. Methylation deficiency causes vitamin B12-associated neuropathy in the pig. J Neurochem 1988;51:1949-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Scott JM, Dinn JJ, Wilson P, et al. Pathogenesis of subacute combined degeneration: a result of methyl group deficiency. Lancet 1981;2:334-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alston TA. Inhibition of vitamin B12-dependent methionine biosynthesis by chloroform and carbon tetrachloride. Biochem Pharmacol 1991;42:R25-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alston TA. Inhibition of vitamin B12-dependent microbial growth by nitrous oxide. Life Sci 1991;48:1591-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alston TA. Chloroform, vitamin B12, and the tragic lives of Robert M. Glover and Horace Wells. Anaesthesia 2004;59:1147-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bhaskar H, Chaudhary R. Vitamin B12 Deficiency due to Chlorofluorocarbon: A Case Report. Case Rep Med 2010;2010:691563. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bauchop T. Inhibition of rumen methanogenesis by methane analogues. J Bacteriol 1967;94:171-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wood JM, Kennedy FS, Wolfe RS. The reaction of multihalogenated hydrocarbons with free and bound reduced vitamin B 12. Biochemistry 1968;7:1707-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alston TA. Don't have a cow! Fight global warming with CFC. Nature 2004;430:965. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Krungkrai J, Webster HK, Yuthavong Y. Characterization of cobalamin-dependent methionine synthase purified from the human malarial parasite, Plasmodium falciparum. Parasitol Res 1989;75:512-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fleischmann E, Lenhardt R, Kurz A, et al. Nitrous oxide and risk of surgical wound infection: a randomised trial. Lancet 2005;366:1101-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kano Y, Sakamoto S, Sakuraya K, et al. Effect of nitrous oxide on human bone marrow cells and its synergistic effect with methionine and methotrexate on functional folate deficiency. Cancer Res 1981;41:4698-701. [PubMed]

- Ermens AA, Kroes AC, Schoester M, et al. Effect of cobalamin inactivation on folate metabolism of leukemic cells. Leuk Res 1988;12:905-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kroes AC, Ermens AA, Lindemans J, et al. Effects of 5-fluorouracil treatment of rat leukemia with concomitant inactivation of cobalamin. Anticancer Res 1986;6:737-42. [PubMed]

- Kroes AC, Lindemans J, Schoester M, et al. Enhanced therapeutic effect of methotrexate in experimental rat leukemia after inactivation of cobalamin (vitamin B12) by nitrous oxide. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 1986;17:114-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Young MJ, Alston TA. Does anesthetic technique influence cancer? J Clin Anesth 2012;24:1-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stoelting RK, Eger EI 2nd. Percutaneous loss of nitrous oxide, cyclopropane, ether and halothane in man. Anesthesiology 1969;30:278-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

夏明

上海交通大学医学院附属第九人民医院麻醉科副主任医师,副教授,硕士研究生导师,人工智能课题组长。Journal of Medical Artificial Inteligence(JMAI)主编,Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Anesthesia(JOMA)执行主编,中华口腔医学会口腔麻醉专业委员会全国常务委员,中华口腔医学会镇静镇痛专委会全国常务委员,中国康复医学会疼痛康复专委会全国委员。(更新时间:2023-02-08)

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)

Cite this article as: Shi J, Alston TA. Antivitamin action of nitrous oxide in OMF surgery—a narrative review. J Oral Maxillofac Anesth 2022;1:34.